TOP UPDATES FOUR PILLARS CINEMA/TV GAMES MANGA/ANIME MUSIC WRITINGS FAQ LINKS

TOP UPDATES FOUR PILLARS CINEMA/TV GAMES MANGA/ANIME MUSIC WRITINGS FAQ LINKS

The Devil, Probably (1977)

In this section, I wish to give some background to appreciating one of my favorite directors: Robert Bresson. This will not be a full scholarly treatment of Bresson and it will not exhaust the things we can say about him. But when asked "What's so great about Bresson?," it can be particularly hard to put the answer into words. And viewers entering the world of Bresson for the first time may have trouble seeing the real power of his films at first glance. I certainly did. The first film I watched by him was Au hasard Balthazar. I didn't really see its greatness. However, I immediately fell in love with the second film by him that I watched: Mouchette. Today I adore every one of his films from Diary of a Country Priest onward. (The two features before it don't really feel like he has settled into his style yet.)

I have trouble choosing a favorite today. For a director whose vision is so concentrated and pure, it's hard to rank one over another. But I usually say that I think his career generally became better as he went on and think that his last two films are among his strongest. I simply prefer the penultimate film, The Devil Probably, for matters of personal preference. Whether you've never seen a Bresson film and want to know where to start or have seen one of his films and it didn't quite click, my advice is the same for those who want to develop a taste for his works: start with Diary of a Country Priest and go chronologically from there.

I here aim to explain what I see as being so incredible about Bresson's films, which is of course largely in accordance with his other admirers. I also want to pay special attention to Bresson's own words published in his series of aphorisms Notes on the Cinematographer, which are often ignored in this discussion.

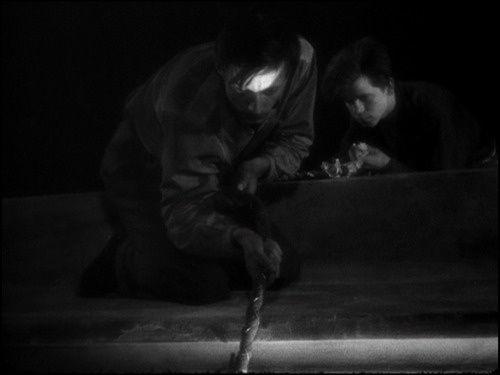

A Man Escaped (1959)

Robert Bresson was born in 1901 and died in 1999. He thus saw nearly the entirety of the 20th century. One of the things that I find most remarkable about Bresson is the incredible single-mindedness of his artistic vision. While he certainly was inspired by events of the 20th century, Bresson's films seem to be steadfastly concerned with their own consistent, rigorous style, no matter when they were made. As a person he was very withdrawn and private. We don't know much about his personal life at all. We know that he was born in a very small town in central France. He studied painting before becoming a director. He was a Resistance fighter and prisoner of war during World War II. He was also a Catholic, though he seems to have had an idiosyncratic view of the faith that was at odds with the establishment in France, especially post-Vatican II. Bresson self-identified as a Jansenist, meaning that he believed in a largely Catholic theology but had a Calvinist view of free will (meaning that he denied that we had it). It is interesting to remember this when looking at the themes of his films.

I will focus on some particularly noteworthy parts of Bresson's style. A lot of these have also become emblematic of modern European "arthouse" films in general, because so many of those guys were influenced by Bresson! Bresson's style also, in my opinion, becomes more "refined" and "pure" over the course of his career. His films become more and more distinctive and clear in these elements, and I do believe that Bresson's later films are his most accomplished. But they are all of such high quality that it's really not by much.

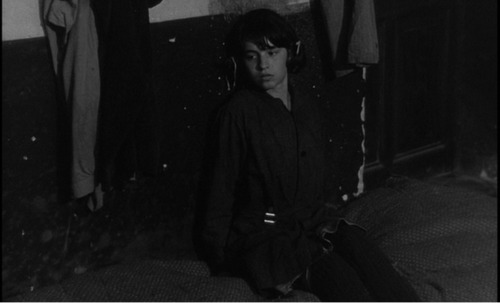

Mouchette (1967)

If you watch one of Bresson's films, the first thing that will probably strike you as unique is the acting... or lack thereof! Bresson was clear about one thing: the kind of "acting" that characterized theater was antithetical to his vision. For Bresson, a kind of acting that emphasized the actor's ability to "put on a performance" was something that was a hanger-on from the medium of theater. Cinema as an art form would remain a pale imitation of theater if it did not have the bravery to disconnect itself from this lineage. So for Bresson, "acting" as we know it must disappear in a film.

Of course, Bresson's films are not documentaries, nor do they solely focus on inanimate objects, so what could there possibly be in place of acting in a film? Well, there are indeed actors in his films, though Bresson himself rejected this term and preferred to call them "models!" All of his films star non-professionals with no "star power" behind their names so as not to distract the audience and get in the way of what was really most important. He intentionally never re-used the same "models" in any of his films in order to never distract from their "acting." And their method of "acting" is truly the final piece of the puzzle here.

Movement from the exterior to the interior. (Actors: movement from the interior to the exterior.)

The thing that matters is not what they show me but what they hide from me and, above all, what they do not suspect is in them.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [1]

It would not be ridiculous to say to your models: "I am inventing you as you are."

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [2]

If you have seen a Bresson film, you know exactly what the experience of watching his "models" is like. If you have not, you can best picture it by understanding his directing technique. Many directors are "perfectionists" who torture their actors by constantly making them repeat their lines and movements until they are 100% perfect. Bresson was the apex of this. He apparently would make his "models" repeat even simple shots like opening a door upwards of 50 times. Shots with dialogue would not uncommonly go into the triple digits. But whereas most directors would do so in order to perfect some technique of "acting," Bresson was quite the opposite. He intentionally wanted his actors to get so tired of the routine that it became so automatic that he squeezed any drop of "acting" out of them. By the end they would be little more than dolls, mouthing words with flat, expressionless faces. It would be very hard to call this "acting." And that was excatly what Bresson wanted. Without any "acting" in the way, the cinematic art was finally fully realized.

Nine-tenths of our movements obey habit and automatism. It is anti-nature to subordinate them to will and to thought.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [3]

This method is deeply off-putting at first. While it is by no means anything like traditional theatrical acting, it is definitely not a move closer to "realism" in acting as we would imagine it either. If someone acted like one of Bresson's models in real life, we would find them very opaque and probably assume they were decidedly neuroatypical. But this is also exactly where Bresson is brilliant. By removing all the "acting" from the "models," we have to do so much more to "fill in" their emotions and "give life" to the proceedings on screen. It is a form of minimalism, one could say. By removing all the "acting," one reduces the medium of cinema to the most stark and essential elements. And there is a profound, austere sense of beauty in that. All of Bresson's style ties back into this attempt to produce something "purely" cinematic, untouched by the concerns of previous arts.

Lancelot du Lac (1974)

Respect man's nature without wishing it more palpable than it is.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [4]

Neither beautify or uglify. Do not denature.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [5]

Bresson called himself a "cinematographer" and described his art primarily as "cinematography." But just as he believed that overly stylized "acting" had the tendency to limit cinema by drawing it back into the realm of theater, he also saw overly stylized camerawork as drawing it back into the realm of photography. For that reason, one will not find unusual angles, bizarre framing, meticulous set design, or other "flashy" forms of visual expression in Bresson's films either. Famously, he insists on images that are not "beautiful" but are "necessary."

The most ordinary word, when put into place, suddenly acquires brilliance. That is the brilliance with which your images must shine.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [6]

Your film's beauty will not be in the images (postcardism) but in the ineffable that they will emanate.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [7]

This, of course, does not mean that Bresson's films cannot be visually appealing. They are quite handsomely framed and composed. But they are not images that "draw attention" to themselves. In their simplicity and directness they achieve a level of "invisibility" and "transparency" that elevates them to something which somehow turns "blandness" into a sort of beauty all its own. It's hard to describe unless you experience it directly.

L'Argent (1983)

My movie is born first in my head, dies on paper; is resuscitated by the living persons and real objects I use, which are killed on film but, placed in a certain order and projected onto a screen, come to life again like flowers in water.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [8]

Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [9]

Your camera passes through faces, provided no mimicry (intentional or not intentional) gets in between. Cinematographic films made of inner movements which are seen.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [10]

What makes Bresson's images unique is not just their "transparency." Something which many note is the "oblique" or "elliptical" nature of his films. What this concretely means is that he often makes viewers fill in the gaps by focusing on things that are "in between" the more "important" or "exciting" or "obvious" parts. I mean this in two senses:

1) Bresson will often have an important element of the story happen off screen and focus only on the lead up or aftermath. Rather than showing a murder or rape, he will only show the events that lead up to it or the result. He will often avoid the more salacious elements of the narrative in a similar way. The Trial of Joan of Arc exclusively focuses on the dispassionate minutiae of the trial, not Joan's mystical visions themselves. Lancelot du Lac is a vision of Camelot which is restricted to the brutality and mundanity of being a professional knight.

2) Bresson will often focus his CAMERA on only "part" of the important scene. The most obvious example is showing only a character's hands performing some action instead of the entire body. If the scene is of a character buying a knife, he will only show the hands making the exchange of money for the weapon. Though he never does this in a way that makes it disorienting. It is truly a minimal amount of data we need to make the connection.

There are many more examples we could bring up in all of Bresson's major works. But by now you should get the picture. All of the above results in films that engage the viewer and cause us to participate. This higher level of attention is quite engrossing and fascinating.

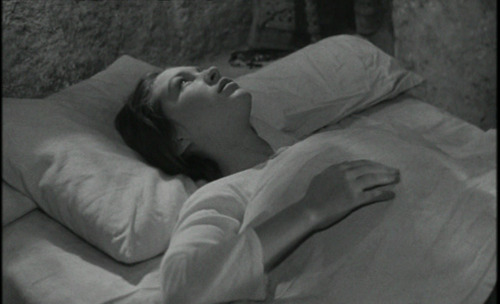

The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

To find a kinship between image, sound and silence. To give them an air of being glad to be together, of having chosen their place. Milton: Silence was pleased.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [11]

Films whose slownesses and silences are indistinguishable from the slownesses and silences of the audience are ruled out.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [12]

One of the ways that Bresson's films feel most immediately "modern" compared to his contemporaries is the complete lack of non-diegetic music. "Diegetic" is an egghead term which basically means music that comes from a source on-screen. So if characters go to a live concert and there's a band playing music in the background, that would be diegetic. But most films use some kind of "soundtrack." This is music as a kind of filler in the background to elicit some form of emotion. Some of the most memorable and beautiful scenes in cinema are combinations of well-arranged music with complimentary imagery. But in spite of these possibilities, Bresson completely rejected the idea of non-diegetic music.

If there is music in Bresson's films, it comes from an on-screen source: a choir singing hymns in a church, young musicians playing songs on the side of the river, children singing nursery rhymes, etc. But even then, Bresson's films don't have a lot of music. There are long stretches of silence in his films. Perhaps the place this stands out most is the opening credits. They usually are one still shot of an area in complete silence with simple, unadorned text on the screen. After all, crediting the "models" is a complete formality for Bresson.

But I misspeak here. I say that Bresson's films have long stretches of silence, but what I really mean is stretches without speech or music. Suddenly, small sounds have an immense weight and presence: footsteps, car engines, birds chirping... And the whole gamut of more mysterious and difficult-to-place sonic textures. This element of Bresson's style is often underrated. But it ties back into the pattern we've seen: Things are elicited and evoked more than directly represented.

Pickpocket (1959)

Practice the precept: find without seeking.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [13]

From the beings and things of nature, washed clean of all art and especially of the art of drama, you will make an art.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [14]

Cinema, radio, television, magazines are a school of inattention: people look without seeing, listen in without hearing.

Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer [15]

So far, I've focused on the way that Bresson leaves us to fill in things and does not spell them out. But at the same time, they are not particularly difficult films to follow from a narrative perspective. The opaque and mysterious nature of the films comes from trying to understand the interior worlds of his models or the "meaning" of his films. You could say that the mystery of his films comes in them being so straightforward. The "meaning" doesn't reveal itself as a tidy soundbyte, but at the same time everything appears to be there on the surface.

One thing that seems to add to this is his choices for source material. Bresson's films are almost all based on pre-existing sources, though he often adapted them in an open fashion. Of the films I consider prime examples of his style, they stack up as follows, though some adaptations are much looser than others:

Diary of a Country Priest (1951): based on the novel of the same name by

Georges Bernanos

A Man Escaped (1956): based on memoirs by Resistance soldier André Devigny

Pickpocket (1959): inspired by Crime and Punishment by Fyodor

Dostoevsky

The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962): based on the historical events in an

extremely authentic fashion (uses real words from the historical transcripts of the

trial)

Au hasard Balthazar (1966): seemingly inspired by a passage from The

Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky, but still should probably be considered an "original"

plot

Mouchette (1967): based on the novel of the same name by Georges Bernanos

Une femme douce (1969): based on the short story of the same name by

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971): based on the short story "White Nights" by

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Lancelot du Lac (1974): based on the parts of the Arthurian legend cycle

centered on Lancelot and Guienevere

The Devil Probably (1977): seemingly Bresson's only completely original

plot

L'Argent (1983): based on The Forged Coupon by Leo Tolstoy

So what can we say about this source material? None of the sources are plays or theatrical productions. No surprises there, as Bresson saw the essential flaw of cinema to be its vestigial dependence on the conventions of theater. It's also obvious that Bresson's favorite author is Dostoevsky, and the two have many parallels. Both tend to focus on the cruelty and spiritual destitution of the world and the way that humans must face it with dignity even if they do not in the end triumph. There is a "tragic sense of life" throughout Bresson's works. But the real interior details of that are hidden from plain sight. And for that reason they are more profound.

But I actually want to argue that what is important here is not so much that Bresson chooses any particular source to adapt and make the plot of his film, but rather the persistent choice he makes to "outsource" his plots to pre-existing source material in general. Of course, few directors write totally original plots for every film they make. But for Bresson, I find this an especially important pattern. It might be surprising that so many of his films rely on literary sources as he made such an important point about disconnecting cinema from prior artforms. But the way I see it is that he does so for a similar reason as choosing non-professionals for his "models." By choosing a pre-existing source, he doesn't let the art of "drama" stand in the way of his vision either. We don't get caught up in thinking of the director being clever in crafting twists and turns in writing the screenplay as if it were a work of literature. It doesn't get in the way of the transcendence achieved through the rigidity of everything I've already mentioned.

Bresson would hate nothing more than being compared to a dramatist of any kind. But I have to make a faux pas, because I've always been struck by the parallels between Bresson's aphorisms and the writings of the most famous Japanese Nou dramatist, Zeami Motokiyo. Perhaps there is something "eastern" about some of Bresson's views about aesthetics. Paul Schrader famously compared Bresson to Ozu Yasujirou (along with Carl Theodor Dreyer). We should be skeptical about going too far with this. But in my own case at least I can say that my understanding of some of the more infamously "difficult" concepts of eastern aesthetics has been helped by my first having been familiar with Bresson. In particular, I will focus on Zeami's conception of what gives Nou plays their impressiveness.

There are some superficial comparisons we can immediately make with Bresson's films and Nou plays. The mask of a Nou performer is immediately distinct from the comic and tragic masks that have become archetypical symbols for the western conception of drama. The Nou mask is constantly placid. It never betrays a hint of emotion. And yet, we fill in so much. In fact, the emotion becomes so much more real to us because we never have it drawn out for us. The two are not perfectly parallel. While the face may be blank on a Nou mask, the Nou actor actually gesticulates and acts quite wild and exaggerated at times in a style that is unimaginable for Bresson's models. But there does seem to be a similar sense of values here. We could say the same about the way that Nou plays are usually pretty minimal in terms of setpieces and props.

Zeami, like Bresson, believed that what was most important was something that had to remain hidden to have real efficacy:

It is often commented on by audiences that "many times a performance is effective when the actor does nothing." Such an accomplishment results from the actor's greatest, most secret skill. From the techniques involved in the Two Basic Arts down to all the gestures and the various kinds of Role Playing, all such skills are based on the abilities found in the actor's body. Thus to speak of an actor "doing nothing" actually signifies that interval which exists between two physical actions. When one examines why this interval "where nothing happens" may seem so fascinating, it is surely because of the fact that, at the bottom, the artist never relaxes his inner tension. At the moment when the dance has stopped, or the chant has ceased, or indeed at any of those intervals that can occur during the performance of a role, or, indeed, during any pause or interval, the actor must never abandon his concentratoin but must keep his consciousness of that inner tension. It is this sense of inner concentration that manifests itself to the audience and makes the moment enjoyable.

Zeami Motokiyo, "Connecting the Arts Through One Intensity of Mind" [x]

"Indeed, when we come to face death, our life might be likened to a puppet on a cart [decorated for a great festival]. As soon as one string is cut, the creature crumbles and fades." Such is the image given of the existence of man, caught in the perpetual flow of life and death. This constructed puppet, on a cart, shows various aspects of himeslf but cannot come to life of itself. It represents a deed performed by moving strings. At the moment when the strings are cut, the figure falls and crumbles. Sarugaku too is an art that makes use of just such artifice. What supports these illusions and gives them life is the intensity of mind of the actor. Yet the existence of this intensity must not be shown directly to the audience. Should they see it, it would be as though they could see the strings of a puppet. Let me repeat again: the actor must make his spirit the strings, and without letting his audience become aware of them, he will draw together the forces of his art.

Zeami Motokiyo, "Connecting the Arts Through One Intensity of Mind" [17]

Bresson's conception of what he wishes to elicit from his models has some echoes of Zeami here. But it's true that Zeami expected much more of his actors. Bresson viewed it much more as his duty to draw this sort of magic out of his models. One might accuse him of denying them agency in the production in comparison, but what he wanted was so original and probably difficult to understand for his contemporaries that it makes sense for him to have taken matters entirely "into his own hands." I am not sure how far the comparison between Bresson and Zeami can be taken, but I hear echoes of Bresson when reading about these ideals of acting. The whole idea of achieving a kind of "non-action" in the Daoist sense and of achieving freedom and spontaneity precisely in the most extreme limitations have echoes of Japanese traditions.

1. Robert Bresson [trans. Jonathan Griffin], Notes on Cinematography, Urizen Books New York, 1977, p. 2

2. Ibid., p. 14

3. Ibid., p. 11

4. Ibid., p. 4

5. Ibid., p. 42

6. Ibid., p. 56

7. Ibid., p. 61

8. Ibid., p. 7

9. Ibid., p. 18

10. Ibid., p. 39

11. Ibid., p. 26

12. Ibid., p. 54

13. Ibid., p. 30

14. Ibid., p. 34

15. Ibid., p. 55

16. Zeami Motokiyo [trans. J. Thomas Rimer & Yamazaki Masakazu] [ed. William Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, & Paul Varley], Sources of Japanese Tradition Volume One: From Earliest Times to 1600, p. 371

17. Ibid., p. 372