TOP UPDATES FOUR PILLARS CINEMA/TV GAMES MANGA/ANIME MUSIC WRITINGS FAQ LINKS

TOP UPDATES FOUR PILLARS CINEMA/TV GAMES MANGA/ANIME MUSIC WRITINGS FAQ LINKS

沈黙 (1971) - 篠田正広

Silence (1971) - Shinoda Masahiro

Shinoda Masahiro's film Silence is an adaptation of Endou Shuusaku's 1966 novel of the same name. I've never read it. Nor have I ever seen the 2016 adaptation of the novel directed by Martin Scorsese. Therefore I intend to treat this film as a standalone work. It deserves it. I've particularly been thinking about this film a lot as I believe it brings several points I have written about into clearer focus, particularly as relates to religions from the east and west and the question of to what degree religion is tied to culture and tradition and the question of whether it can be translated and how.

I will try to not spend this review retelling the story of the film point-by-point. Spoilers will be inevitable in this discussion, but I will mark them accordingly. But the essential points are as follows: The film follows a Jesuit missionary named Rodrigo from Portugal who lands in Japan. He and his associate choose to spread the gospel there even after Christianity has been formally banned and all the Japanese Christians have been driven into hiding. They live hard lives. They are loved and cherished by Japanese Christians who are desperate for spiritual leaders, but must remain well out of the eyes of the shouguns. Eventually, Rodrigo is captured and faces the same fate as all the Japanese Christians: the fumi-e. He is required to trample on an image of Jesus in order to demonstrate his lack of faith. Failure to do so will result in his torture and death.

Shinoda's film takes place entirely in Japan, but reminds us of the condition that these Jesuits lived in. The exact time period of the film is obscure, but it seems to be the very early 17th century. The two missionaries must sneak their way onto the island, which suggests that Japan has already been formally closed to the outside world. This places the time after 1603, but before 1650 as one of the historical figures in it is still alive. Let us remember Europe during this period: What was once honored as a united "Christendom" was itself not too different from the contemporary Sengoku Period of Japan: a series of warring faiths each fighting for control and authority. This had been continuing for almost 100 years after Martin Luther's theses in 1517.

The story of "the Reformation" in English-speaking countries is often unfairly biased as a story of free-thinking, forward-looking men in Protestant countries casting off the superstition, empty ritual, and authoritarian rule of the Catholic church. But what does the word "Reformation" truly imply? A stripping away of all but what is essential. In so doing, most of the Protestant Reformers were not looking forward, but were looking back very far indeed to find what the true core of the faith was. And I do not say this as a term of disparagement. All truly great renewal and progress only comes when we are in touch with what is most primordial and originary. We can only innovate by returning to the source.

And in this sense, it was by no means only the Protestants who experienced such a "Reformation." The parallel movements in the Catholic church are often called a "Counter-Reformation," but this term is somewhat disparaging. For these reforms did not occur only in response to Protestant developments. They were for the most part born out of the same concern and motivation of the Protestants: a desire to return to the source. One man who experienced such a profound experience of the source and core of the Christian faith was named Ignatius of Loyola. He founded the order known as the Society of Jesus or Jesuits. One of the co-founders, Francis Xavier, lead the first Christian mission to Japan some 50 years before the events of this film take place.

A caricature of the time was of priests and churchmen as fat and happy, exploiting the sweat and labor of the common people in order to live in luxury and idle away, with an air of superiority on top of that. Well, no matter what one thinks of them, one could not charge the Jesuits with this picture. These guys were hardcore. They saw themselves as soldiers of god, and the conditions they lived in brought the point home: They put aside prospects of wealth and comfort, choosing to be sent to the most dangerous, alien, far corners of the earth and risk their lives to spread the gospel. And after Christianity was officially outlawed in Japan, few places were more dangerous for them.

The Christianity that emerges under Rodrigo's stewardship in Japan does not look like the Christianity in Rome. It does not occur in lovely, baroque churches, but in peasant hovels and musty caves. It is secret and private. There is very little hierarchy in the church, as it is a faith of the downtrodden and oppressed. The Jesuit leaders prize poverty and humility. However, what is so interesting is that this is perhaps the closest representation of the earliest apostolic days of Christianity that we could experience. The earliest Christians in Rome certainly lived like this. It seems that it was only in circumstances like this that the purest version of Christ's teachings could emerge.

And the results are obvious. The shouguns in this film realize what the Romans realized as well: Christianity, in its purest form, destroys all hierarchy, all authority, all governments, all societies. When a peasant thinks that all are one before god, the authority of the shougun cannot survive with this. As Paul famously claimed: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus." [1]. Frightening words for a feudal lord!

One one hand, then, it is clear why Rodrigo is so convinced of the righteousness of his mission. However, he is a human, and it seems as though on any intuitively human level, his spreading of the faith only causes suffering. The peasants he teaches keep getting found out, rounded up, and executed. It separates families and disrupts all order. A crisis of faith seems to subtly be brewing under the surface. Many of these tensions come to a head when Rodrigo is finally captured and imprisoned by Inoue, the Magistrate of Nagasaki.

However, Magistrate Inoue is as thoughtful as he is rigid to his rules. He will not let Rodrigo be imprisoned or tortured without giving him a chance to recant and without giving him good reasons why. The words of the Magistrate may as well be a voice in Rodrigo's own head. The Magistrate claims that the seeds of Christianity are clearly not taking root in Japan and that his effort seems futile. Rodrigo contends that they only do not take root because they are being prevented from doing so by the authorities. But the Magistrate contends that Christianity is a fitting faith for people in Europe, but not for those in Japan. He says that each of them should protect their faiths in their own lands for the common good of humanity. But Rodrigo's ultimate position remains the same:

"According to our way of thinking, truth is universal. If we did not believe this, why should so many missionaries endure these hardships? If a doctrine be right in Portugal but not right in Japan, then we cannot call it truth!"

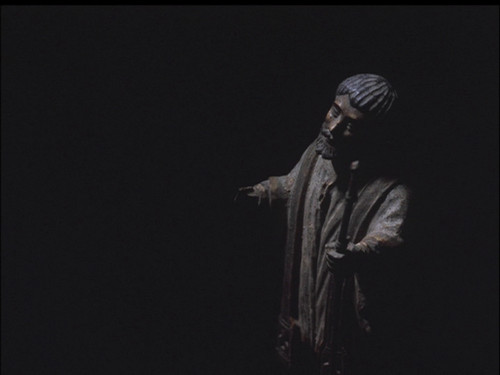

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is the treatment of the fumi-e. This was a ritual that the Japanese authorities did to find and persecute Christians, and it was quite effective. They presented a plaque containing an image of Jesus or Mary to the suspected Christian, and the suspect would have to step on it in order to show that they were not Christians. In the film, the suspects are horrified at the prospect of performing the fumi-e. Many choose to die instead of stepping on the image. Several in the film are tied to posts during low tide and left to drown when the tide comes in, among other gruesome torture methods. Such was the case even after the authorities in one case at least explicitly tell them "you are free to believe whatever you wish, this action is a mere formality."

I watched this film for a third time with my father, and his response was telling. Now, I love my father and am not bringing this up to say that he is wrong or shame him. In fact, seeing his reaction to the film gave me a lot of insight, despite the fact that it was so different from mine. My father grew up in a fundamentalist Pentecostal church and grew to hate the church and left it in his teens. He became a committed atheist and has been very critical of organized religion ever sense. His response was something like "all they have to do is step on a piece of metal which means nothing and then they can be safe and happy, which is what Jesus would have wanted." I think in a sense, this reaction explains a lot. Ironically, I think that it is my atheistic father who has a far more "Christian" worldview here and the Japanese Christians in the film as having a far more "Japanese" or "Shintouist" one. Why? Because one believes that objects can be holy and sacred, and the other does not.

In much of our modern western world, we still have inherited this distrust of appreciating objects for fear that they could become "idols." We have remained afraid of the spiritual power of objects far after we have cast off the Abrahamic yoke. These Japanese on the other hand were still deeply devoted to their most original religion of animism. For even though the Japanese believed in Christ as their savior, they could not abandon the most fundamentally engrained and ancient Japanese spiritual belief: that objects have spirits in them. While a Christian in Europe could justify standing on a plaque because it was a "mere" object, the most fundamental religious compulsion for these Japanese was to honor and love the objects around them, and so they could not. Which brings me to the climax of the film, where all these points are tied together.

!!!---SPOILERS FROM THIS POINT ON---!!!

From the beginning of the film, Rodrigo has been concerned about the condition of his prior mentor, Cristóvão Ferreira, who made his way to Japan before him but had gone missing. Ferreira was an actual historical figure, and his depiction here is largely accurate in terms of biographical details. As Rodrigo proves himself too stubborn to recant his faith, he is introduced to the man he searched for: Ferreira (in the film he is played by Tanba Tetsurou in fairly unconvincing western makeup, but you just have to look through that for what is a truly amazing performance). But his hopes for salvation and guidance are dashed. Ferreira has done the unthinkable: he has become an apostate and renounced Christianity, even going so far as to perform the fumi-e. He now works as a servant of the Magistrate in his inquisition.

A dialogue between Rodrigo and Ferreira is the most important scene in the film in my opinion. When Rodrigo accuses Ferreira of weakness for his apostasy, Ferreira makes it clear that Rodrigo speaks too naively to one who has spent 20 years trying to spread the faith in Japan. He says that Japan is a wretched swamp for the seeds of the Christian faith, and that there is no hope of it ever taking root in this land. And yet, he does not blame the authorities for it. He is not like Rodrigo who believes that with the mere removal of the political systems of repression, Christianity would thrive. For he says that even in the times before Christianity was repressed in Japan, it had never really taken root:

Ferreira: "This country is like a swamp. You will learn that. A swamp more terrifying than we ever imagined. A terrifying swamp where any seedling planted is destined to rot. The leaves wither and the plant dies. It was in such a terrifying swamp that we first sowed the seeds of Christianity."

Rodrigo: "There was a time when that sapling grew and spread its leafy branches wide."

Ferreira: "That is not our God."

Rodrigo: "You deny even things that must never be denied!"

Ferreira: "That is not true. It is not our God, but their gods that these people believe in. We didn't realize that for a long time. We thought they could become Christians. Maybe you've seen it already... how the farmers worship the Kannon Buddha as Mary. They love that pagan figure more than the teachings of our Lord. Probably no one will believe what I say. Not only you. Neither will the Jesuits in Goa or Macao, nor all the holy fathers in Rome! No one will believe me!

Rodrigo: "When Saint Francis Xavier was in Japan, I'm sure he never thought the way you do! He said the Japanese people are as intelligent as any race in any country in Europe!"

Ferreira: "The saint never once noticed the fact... Xavier taught them about Deus, but the Japanese changed it into their own sun god. They call it Dainichi, and it became their god. They bend and change our God into something else, something quite different."

In short, Ferreira realizes that the Japanese peasants he tried to "convert" could never really convert, because they could never really understand the gospel as he did, which was ultimately what the act of conversion would really mean. When considering this example, I remember Willard Van Orman Quine's famous "gavagai" thought experiment. Quine puts forward the scenario of a linguist living in a tribe that is, until now, uncontacted. No one on the "outside world" can speak their language. One of the tribe's members looks at a rabbit run past the two of them. The tribesman looks a the rabbit and says "gavagai!" Now, it might seem natural to assume that in this case, the word "gavagai" means "rabbit." Another rabbit with a different pattern runs by and the tribesman again says "gavagai," which seems to close the case.

But is that really enough to go by? If this tribe hunted rabbits, could not "gavagai" be a term for "food?" Nor can we be sure that the native has a similar metaphysical foundation. Perhaps the tribe believes that we are dealing with a process rather than a substance. Perhaps "gavagai" could be translated as "it is rabbiting" or "a manifestation of rabbithood" or "a rabbit time-slice" or "undetached rabbit-parts!" None of these would be incompatible with the actual evidence we have. Whenever there are undetached rabbit-parts, there is also what we call a "rabbit." Maybe some could be ruled out. Perhaps the native sees a badger and also says "gavagai." But now what does the word mean? Four legged animal? Mammal? Stealer of food? Perhaps he uses a different word for an infant rabbit. But does this mean that "gavagai" must only mean a fully-grown rabbit? Or could it mean any fully-grown animal with two ears? For any possible interpretation, it seems as though there are an infinite number of others that equally accord with the evidence.

The ultimate point for Quine is a kind of radical uncertainty not just about what the native might be thinking, but what sort of ontological reference point he could be thinking it about. How could we ever be sure if he thought in terms of "rabbits" or "rabbit-parts" or "rabbit-processes" if we aren't even sure as to what the referent of his language is? But perhaps the other side to that point is that ultimately, none of these ontological foundations mean much for our actual communication and shared existence in the same world. For this issue does not stop at the native and the translator. The same indeterminacy of translation would apply even for people who speak languages like French or Spanish or indeed even for speakers of the same language. Reference is always indeterminate. [2]

And now we see Ferreira's point about the act of conversion. How would he ever know if the Japanese were worshipping "his" god? And if that were the case, how did he know that he was worshipping "his" god? How does he know that he worships the same god as the apostles? How does he know that all the European peoples have not dressed up Zeus and Hera and all their pagan traditions in Christian clothes in the same manner he accuses the Japanese of doing? Now Rodrigo's claim takes on a new meaning. "If a doctrine be right in Portugal but not right in Japan, then we cannot call it truth!" Ferreira agrees wholeheartedly. For that very reason, the Christian dogma cannot be considered a truth. This lead him to apostasy.

In the end, Rodrigo is tortured along with several other Christians. And he is given an ultimatum: If he performs the fumi-e, the three other men alongside him will be spared and allowed to live. Ferreira, who went through the same ordeal before his renunciation, urges Rodrigo to give up and listen to the humanity inside him that yearns to save the three men. Ferreira drives the point home in no uncertain terms:

"If Christ were here at this moment, I feel sure, for the sake of those men, he would apostatize."

Rodrigo finally goes through with the hardest action for him to do: he steps on the likeness of the savior who he loves. I have heard in the original novel that he has a mystical experience of sorts and the Christ on the plaque speaks to him, forgiving him and urging him to trample on him for the sake of love. In the film, there is no such indication of it. The whole affair takes place in a palpable silence. I think this was a very wise choice. It forces us to "listen" to the silence of the object and hear it ourselves.

Rodrigo dies as a Christian at that moment. He is reborn in quite uncertain terms. He is given the name of a Japanese Christian who died and takes his place, marrying his widow, just as Ferreira had done years earlier. His life does not seem unpleasant. He consults with the Magistrate to identify Christian activities from one who knows them better than anyone. He shares his other much-wanted western erudition in scientific matters like astronomy and physics. The days seem relatively tranquil. What is he in his heart? A Christian? An atheist? A Shintouist? A Buddhist? Can it be named? Did he ever really share his religion with anyone else? Is it even possible to?

!!!---SPOILERS END HERE---!!!

Silence is a remarkably beautiful film in terms of its visual and sonic qualities. It takes place in a quite verdant, rich Nagasaki. Rodrigo arrives in secret at the coast, and he rarely sees the cities of Japan. He experiences the rugged beauty of its nature and the people who live in closest contact with it. The Japanese use the phrase 八百万の神 or "the eight million kami" to express the uncountably large number of gods present in all phenomena in nature. Silence displays this beautifully. It feels as though from his first steps onto the island, the native gods are trying to assert their providence over the land in contrast to the one that Rodrigo brings.

And yet, perhaps a deeper point is that this feeling of love and beauty that overflows in nature is overwhelmingly ineffable. Perhaps that is the ultimate truth, and that the rituals we apply around it are conditional and a matter of evolved culture. For me, this love and wonder at the natural world becomes expressed in what is called animism or Shintou and it is the highest faith. And I believe that no one recognized this more clearly than the real, historical Cristóvão Ferreira, who summed up his post-apostasy religious worldview as follows:

Viewing the world around us we see that everything is endowed with its own nature and merit; bird or beast, insect or fish, grass or tree, earth or stone, air or water, each one has its natural quality and merit. All this is work of Natura. Man stands at the head of all existence and Heaven has endowed mankind with the natural faculties of charity, justice, propriety, sagacity. Therefore mankind discriminates between good and bad, as well as aspires after equanimity. [3]

If you are at all interested in the themes I have mentioned, please watch Silence. You will not regret it.

1. Galatians 3:28, King James Version, BibleGateway.

2. See this article for a more in-depth discussion of Quine's philosophy: Ali Hossein Khani, "The Indeterminacy of Translation and Radical Interpretation", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

3. Hubert Cieslik, "The Case of Christovão Ferreira", Monumenta Nipponica Vol. 29, 1974, p. 1-54.